When America Refused To Hold White Supremacist Terrorists Accountable, It Made Itself Into A Klan Country.

In her analysis of Reconstruction, Kidada Williams reminds us that a better world has always been possible.

***This essay first appeared in and is reprinted here with the permission of the Bucks County Beacon.***

Time and again, one word jumps out from the stunning prose of Kidada Williams: Confederate. While the term is a staple of Civil War literature, it has less often been applied to Reconstruction—the period of progressive reforms and white supremacist backlash after the Civil War. Reconstruction, after all, came after the Confederacy had surrendered, crushed under the weight of Black Southern demands for freedom and their widespread willingness to serve in the military to achieve it. Yet as Williams reminds us, Reconstruction bore not only the fruits of Black organizing and legislative work—fruits that included integrated schools and public transit along with universal male suffrage—but also the poison of mass white supremacist violence and judicial connivance, what she frequently reminds readers was a “war after the war.” In a very real sense, the white conservatives who retook power by creating the largest organized terrorism campaign in U.S. history were Confederates. The Klan Country they created by destroying Reconstruction was a Neo-Confederacy in all but the narrowest legal terms.

While the prospect of white conservatives using paramilitary violence along with accomplices in legislatures and on the courts to walk back civil rights might seem distressingly familiar on its own, Williams leaves little room for doubt about the importance of her analysis for us today. “Why this story right now,” she asks, “in a climate in which we’re bombarded with police killings of unarmed Black people, vigilante attacks, mass shootings, and Black people’s premature death from racism?” All of this might be too much, Williams concedes, but “listening—really listening—to survivors of racist violence in the past holds lessons for our current moment” (xxiii). Her clear framing of the political ideology of the era—employing terms like “progressive” and “white conservative” to help readers make sense of the parties’ changing stance on racial equality—and emphasizing the fragile nature of multiracial democracy and the danger of allowing white vigilantes and insurrectionists to operate with impunity presents readers with a fresh and relevant telling of the struggle for equality during Reconstruction. “We must explore the violence [that survivors of Klan attacks] detailed because the forces driving it persist,” Williams explains. Doing so “might inspire us to assume greater responsibility for confronting racist violence and building a better future” (xxv). This inherited struggle lies at the heart of Reconstruction and offers us a chance today to redeem our democracy and one another on behalf of both justice and survival.

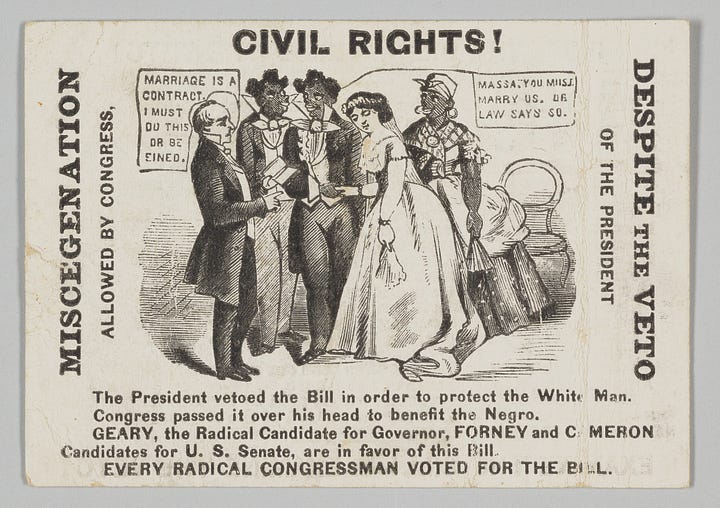

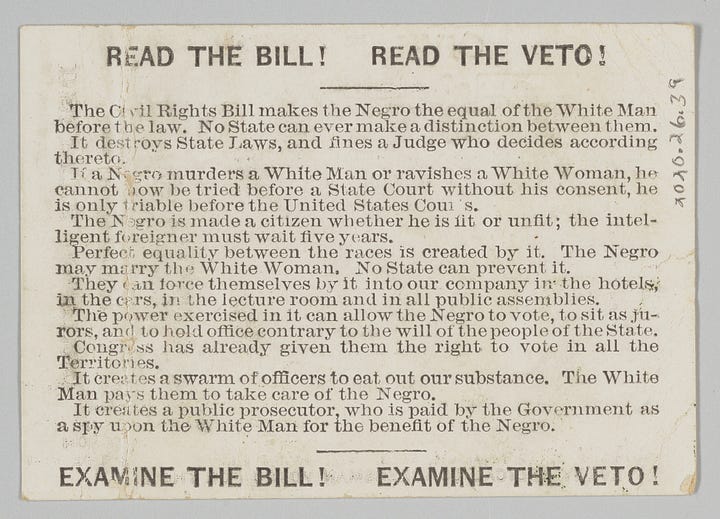

In I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War against Reconstruction, Williams gives a harrowing account of these Reconstruction years of multiracial democracy from the testimonies of ordinary Black Southerners who transformed the world of slavery into one of equality and opportunity for all. After winning their freedom, Black Southerners fought for “the right to marry, have independent family homes, chart a family’s course, secure dignified work and reap the rewards of one’s labor, acquire land, open a business or work from home, accumulate wealth in property, and attend school” (3). While we might take rights like these for granted, they had been explicitly denied enslaved people and later undermined by former enslavers through the Black Codes during the brief period of “self-Reconstruction” following the war. During this period, white conservatives used indiscriminate mass violence along with a new slate of laws banning Black Southerners from owning property, owning guns, moving freely, or becoming self-employed. White conservatives also carried out massacres in Memphis and New Orleans, planned and executed by local police departments. It was not until Black Southerners won the right to vote in 1867 that their new, fuller vision of freedom and equality became possible, written into law by formerly enslaved people and their radical comrades.

Although the book focuses on the testimony of Black Southerners who survived Klan violence, it’s worth stopping to consider the scope of Black Americans’ victories from the spring of 1867 through the fall of 1868.

Black radicals spearheaded nationwide organizing for equality, forming organizations like the National Equal Rights League founded by Frederick Douglass and holding Colored Conventions and state-level Equal Rights League meetings all across the U.S., from Connecticut to California. One such organization, the Friends of Universal Suffrage in New Orleans, led a movement to rewrite the state constitution in 1866, when they were gunned down by New Orleans police and white vigilantes for daring to support universal suffrage. Their visionary work and sacrifice helped inspire radicals in Congress to pass the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which enfranchised Black Southerners and gave them the opportunity to rewrite their state constitutions. Black Americans rose to the opportunity, sending 267 Black delegates to constitutional conventions across the South.

Black delegates in Mississippi guaranteed rights to property, due process, public schools, and removed property qualifications for public office and jurors. Delegates in Louisiana went a step further, declaring that “all persons shall enjoy equal rights and privileges upon any conveyance of a public character; and all places of business, or of public resort… without distinction or discrimination on account of race or color,” articulating rights that Black activists would make real despite violent white conservative resistance through Freedom Rides and Sit-Ins a century later. In South Carolina, delegates not only shielded the state’s poorest residents from taxation and bankruptcy through three homestead exemptions, but also resolved to petition Congress for one million dollars to distribute land to formerly enslaved people and their poor white neighbors.

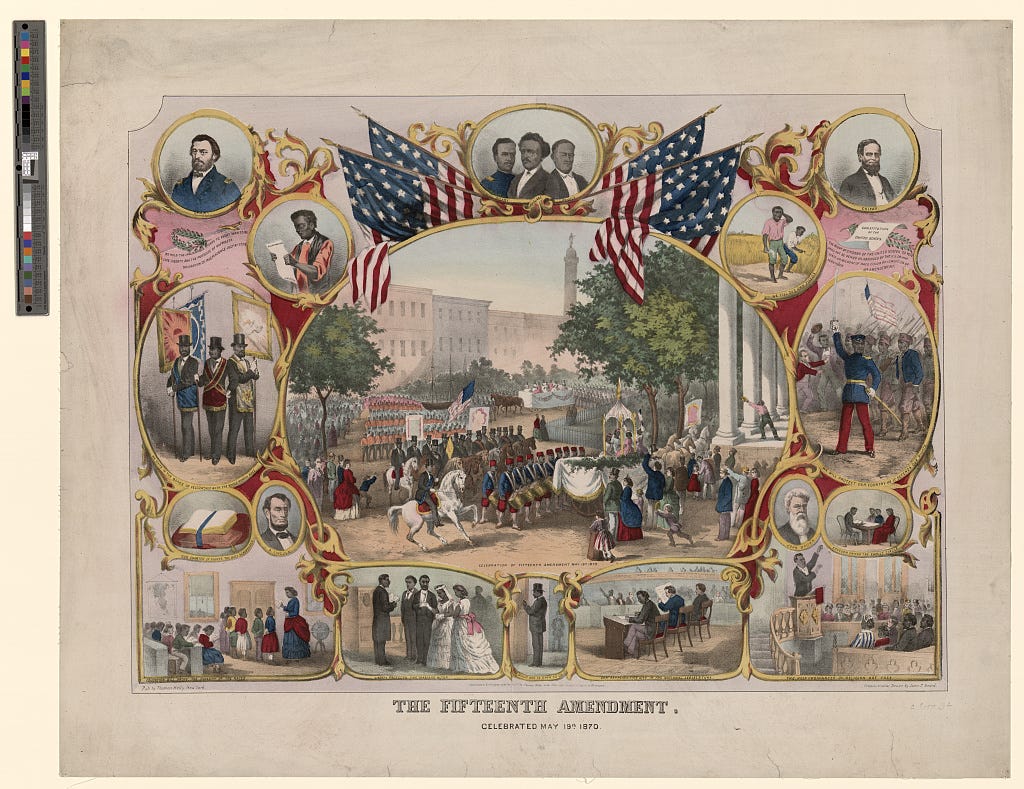

All told, Black Southerners contributed 1517 of their kith and kin to public office from 1867 through 1877 after having sent nearly 200,000 of their fathers, sons, brothers, and cousins to serve in the armed forces. Black thinkers, organizers, and officials demanded and helped pass the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, expanding rights of citizenship in ways the U.S. has yet to fully embrace 150 years later. Despite making up just fourteen percent of the national population, Black Americans had successfully transformed the legal and political landscape of the U.S., creating a new era of democracy and an array of public services that would benefit the many, regardless of race. Their successes—owning property, building schools, starting families, gaining fair wages, and rewriting state laws as legislators and officials—were nothing less than unthinkable for the Confederates in their midst.

It was the successes of Black voters and politicians that inspired the first Klan and offered Americans two distinct paths forward—multiracial democracy or fascism.

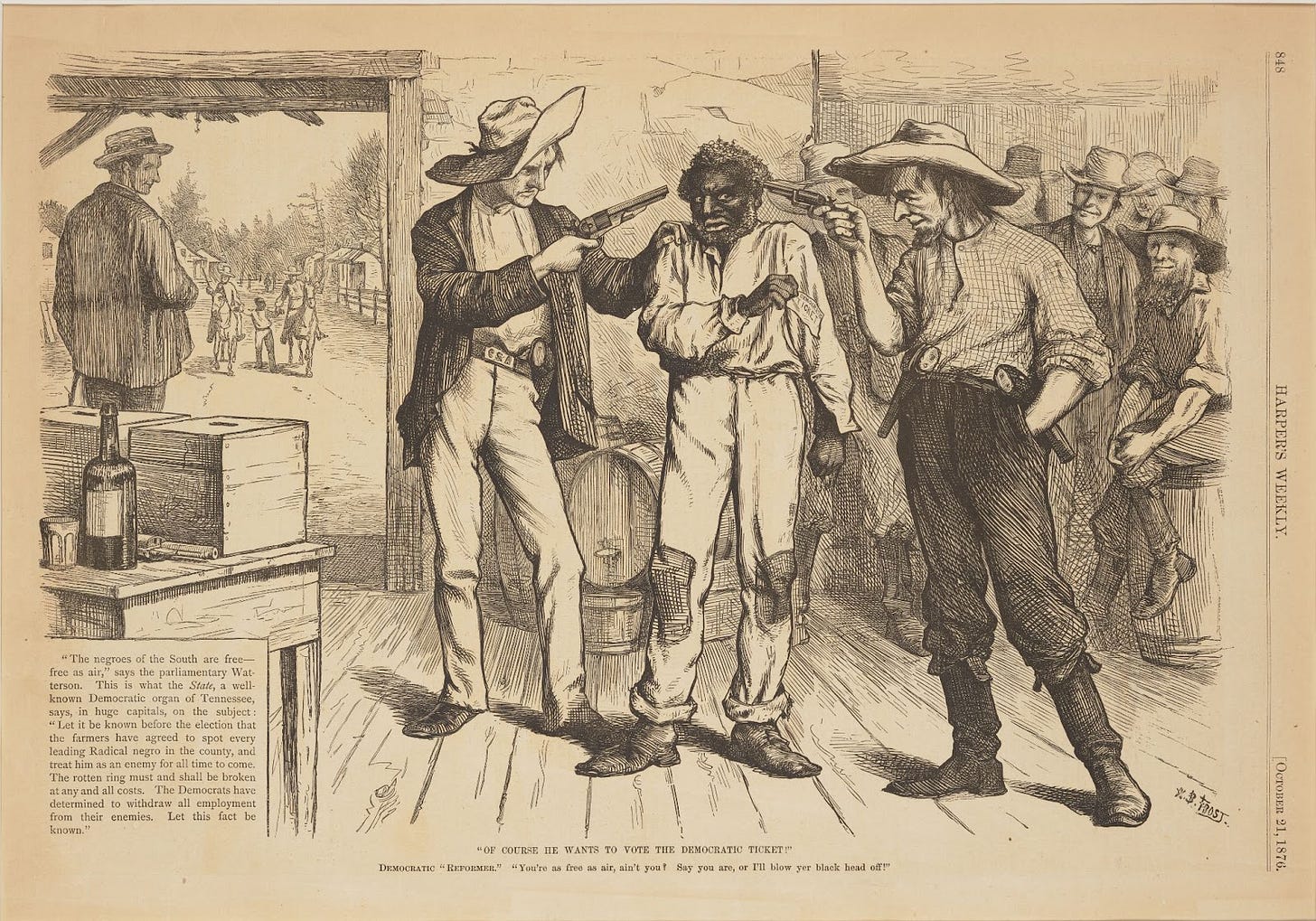

One consistent point of emphasis for Williams is that the white supremacist violence that coalesced in the Klan and ultimately undermined Reconstruction represented a direct response to Black American successes. This runs counter to popularized “hate-in-their-heart” depictions of the Klan as instruments of indiscriminate racist violence, directed at any racialized target within their grasp. As Williams painstakingly shows, the Klan chose their targets carefully, singling out Black politicians, teachers, and preachers for violence with special depravity. Colombus Jeter, for example, was targeted by the Klan for running a school in Douglas County, Georgia (81) while Wallace Fowler was attacked because he had told a white boy to stop stealing his watermelons in Glenn Spring, South Carolina (57). The Klan “visited” Warren Jones for asking his employer for his wages (58) and attacked Edward Crosby for trying to vote for progressive candidates (53). As Williams explains through hundreds of examples, the attacks “conveyed white southerners’ rejection of Black people’s right to have rights; not just their legal equality, the vote, or their service in elected office, but life, security, family, home, property, education, religion, and community—all the freedoms formerly enslaved people cherished and had achieved” (53).

I Saw Death Coming not only documents the white conservative violence that destroyed Reconstruction, but also demonstrates the impact of that violence in targeted communities. The thousands of midnight raids conducted by the Klan during Reconstruction destroyed vibrant Black communities. Even in instances where raids did not result in fatalities, targeted families had enormous difficulty going on with their lives, and the majority never recovered from the experience, bodily, psychologically, or financially. Confronted by dozens of heavily armed and depraved white men in the middle of the night, Black Southerners had little chance of fighting back as their property was pillaged, their family members beaten into unconsciousness, and their homes torched. White conservatives operated with impunity as they controlled local law enforcement and had stacked local courts with sympathetic right wing judges. Within that environment, Williams explains, the ashen structures and hastily buried loved ones served as a haunting reminder to those who remained that, in the words of the Dred Scott ruling, they “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

A group we might today term white moderates represented one of the most substantial obstacles to Reconstruction in Williams’ telling. While committed radicals played an important role in helping create the potential for equality in Reconstruction, the vast majority of white Americans ranged from ambivalent to openly hostile to expanding civil rights to Black Americans. Histories of “reconciliation”—the period of recreating white national unity after Reconstruction—have long noted that a fanatical devotion to anti-Blackness represented something of a civic religion that enabled white Northerners, Southerners, and Westerners to unite around common beliefs in white supremacy.

Williams gives further weight to this argument in her close reading of Black Southerners’ testimony in the Congressional inquiry into Klan activities in the Deep South. White Congressional leaders knew that the Klan had orchestrated thousands of attacks on Black voters, politicians, property-owners, and their families, but took little action other than recording the testimony of their victims. This tactic only worsened the attacks as white conservatives came to understand that they could act with impunity—that everyone understood the severity of their depredations and would take little if any serious action to stop them.

We confront a Republican Party today wholly committed to the very crimes that destroyed Reconstruction and created an apartheid state that would last the better part of a century. In late 2020 and early 2021, the Republican Party orchestrated a sprawling fake elector scheme not unlike the one that white conservatives deployed time and again during Reconstruction. Republican legislatures passed the largest wave of voter suppression laws we’ve seen since the 1890s, when white conservatives formally eliminated Black suffrage in a move endorsed by a right-wing Supreme Court in 1898. Republican politicians regularly traffic in the racist and nativist language of the first Klan, dehumanizing Black Americans and other targeted groups with racist dog whistles and hysterics about “an invasion” of nonwhite Americans while invoking fears of the fascist “great replacement” conspiracy. Their race-baiting tactics have already inspired hate groups and right-wing terrorist attacks. The likely Republican nominee orchestrated an insurrection after the last election and regularly incites violence to intimidate his opponents and discourage accountability for his crimes. We face, in other words, a fascist political party committed to undoing the democratic and civil rights victories of the last sixty years.

We know that the greatest democratic reforms of the Reconstruction era were spearheaded by Black Americans themselves. But what might have happened if white Americans had demanded democracy and equality as the threshold for peace? What might we accomplish if—for ourselves and one another—we demand nothing less than equality today? It is long past time that we find out.