Why I Use The F Word (And You Should Too)

We have a fascism problem. Solving it requires that we correctly identify this problem and the dangers it creates.

What does abortion criminalization have to do with voter suppression or with denying election defeats (and only defeats)? What does resistance to COVID mitigation have to do with attacking educators’ ability to teach about the history of racism in the U.S.? What does targeting LGBTQ & especially trans folks have to do with laws allowing motorists to run over protesters? On their surface, these issues seem totally unrelated, but each reflects a suppressionist and eliminationist logic that is the defining feature of fascism. They are also each central policy positions of today’s Republican Party.

Indeed, whether it’s the extremist Court that just overturned the basis for all of its twentieth century civil rights rulings, the 1/6 Insurrection orchestrated by the Republican Party, or the various state-level laws restricting the right to vote, teach, protest, terminate pregnancies, and exist as a queer person, it has become increasingly clear that something is deeply wrong with the Republican Party. That something is fascism.

What do we mean by the word fascist?

If you consume much TV or news, you might have some idea that fascists are loud, combative people who just really like uniforms. Fascists, in this telling, are simply people with bad manners and (so we’re told) a bad education—a handful of bad individuals—bad “apples,” if you will.

The problem with this way of understanding the term is that it fails to account for systems of power. After all, fascists don’t say they want a world where they can have bad manners—the world they describe is one in which they alone wield power—the power to determine who deserves full membership in the state and who gets excluded from that membership and its rights and protections.

While some far-right obsessions— “cancel culture,” for example—appear at face value to be about some inalienable right to have bad manners and be recklessly ignorant of the past and the world around you, the central feature of these claims always boil down to power. Their missives—laced heavily with nostalgia, another animating feature of fascism—opine the imagined loss of the power to promote racist and sexist ideas without any social consequences (there are already no legal consequences). The claims, in other words, are about power. This is why these bespoke reactionaries (you know the ones) fail to counter the anti-“CRT” movement responsible for state laws and ordinances that suppress and criminalize teaching about our racist and repressive history in the U.S. Doing so would be contrary to their interests, because the anti-“CRT” and “cancel culture” movements actually work in tandem to promote the ideas of white backlash—rigid hierarchies and norms enforced by unimpeachable systems of power.

So if we cannot understand fascists as simply “bad apples” (who spoil the whole bunch, but I digress), how do we make sense of fascism and its demands? If it isn’t just poorly-informed (mostly) white people who really like uniforms, what is it?

As fascist dictator Benito Mussolini explained in his 1932 essay, “The Doctrine of Fascism,” the defining feature of fascism is “it[s] will to power, its will to live, its attitude toward violence, and its value.” Fascism first and foremost, in Mussolini’s thinking, is concerned with seizing and exercising power, with exercising unilateral, eliminationist violence against its opponents. “Anti-individualistic,” he explained, “the Fascist conception of life stresses the importance of the State and accepts the individual only in so far as his interests coincide with those of the State.” In Mussolini’s framework, there is no room for personal preferences, beliefs, or convictions. Under fascism, the state requires total subordination.

Let’s pause and consider Mussolini’s point by examining two issues less commonly associated with fascism in our public discourse: sex and gender. While we rightly consider race and ethnicity as central to fascist projects, policing sex and gender norms are no less crucial. While Hitler initially welcomed openly gay Ernst Röhm as his closest advisor, for example, he had Röhm and others rounded up and killed shortly after he was elected chancellor. That’s both an illustration of power—Hitler needed Röhm to organize the brownshirts (until he didn’t)—and of the relationship between fascism and patriarchal mythology. As Jason Stanley argues exhaustively in the first chapter of How Fascism Works, fascist mythologies tie the imagined greatness of the past to rigid patriarchal power and gender roles. So when, for instance, we see Republicans calling Democrats a “Party of Groomers” (not linking) for supporting LGBTQ rights, what we are seeing is not some weird sexual fixation but a tactic of scapegoating and myth-making used by fascists for a century.

The Republican Party’s recent assaults on LGBTQ rights and reproductive autonomy for women and gender nonconforming folks with uteruses are often framed as a commitment to old time religion—to fundamentalist and austere Christian norms and practices. These claims too—that it’s not fascism if it’s religion—hide the ways that fascists have long used religion to produce a fascist national mythology and as a weapon to exclude, suppress, or eliminate those seeking freedom of thought and action. Mussolini explains this tactic:

The Fascist State is not indifferent to religious phenomena in general nor does it maintain an attitude of indifference to Roman Catholicism, the special, positive religion of Italians. The State has not got a theology but it has a moral code. The Fascist State sees in religion one of the deepest of spiritual manifestations and for this reason it not only respects religion but defends and protects it.

As the Italian fascist dictator makes clear, religious devotion is not only compatible with the suppressionist vision of the fascist state, but can actually help accelerate it. Note his reference to “the special, positive religion of the Italians.” Here Mussolini invokes the idea of a national religion—Roman Catholicism—that gives life to the nostalgic mythologies around national character and greatness created to serve the regime and suppress outsiders. Mussolini’s argument is echoed almost verbatim in the logic of Samuel Alito’s insistence in Dobbs that rights only exist which are “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.” In the United States, that argument limits our rights to those recognized in our country’s deeply racist and patriarchal history.

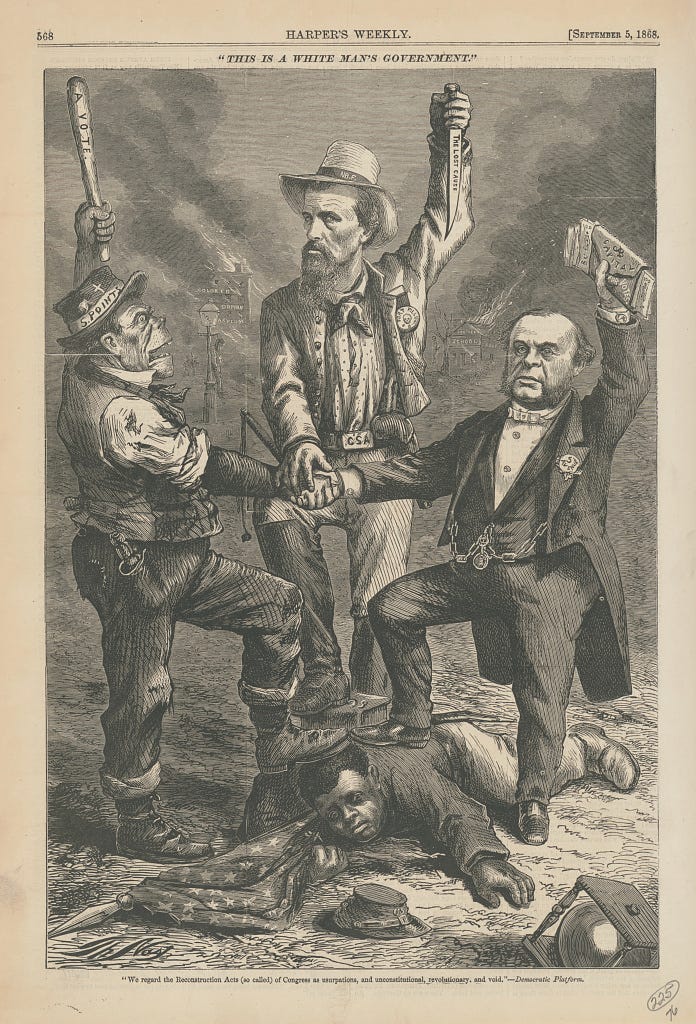

While it’s understandable that so many people accept the idea promoted by our institutions—that fascism is primarily an individual (or aesthetic!!!) problem—that’s not how scholars or fascists themselves view the ideology or its goals. Instead, when we talk about fascism, what we’re really talking about is the relationship between 1) a nostalgia for a deeply oppressive past and 2) the power to use institutions to silence, expel, or eliminate anyone who exists outside of this imagined past, whether it’s the “Christian nation” of today’s Republican Party or the “white man’s country” of white conservatisms past.

Fascists seek total control over their opponents. Fascist movements, then, are suppressionist and eliminationist by design. There are no legitimate alternative ideas or movements under a fascist worldview. As Mussolini put it, “individuals and groups are admissible in so far as they come within the State.” Thus individuals must be subsumed by loyalty to the state and adherence to its values and norms or be subject to its eliminationist and suppressionist initiatives and violence.

The hyper-individual, “bad apples” version of fascism uses a liberal, individual frame to (mis)interpret fascist initiatives. The implied solutions of civility and education to this “bad apples” rendering of fascism, then, misunderstand the goals of fascism and its historical iterations. Pro-Trump vigilantes illustrated this point well when they told Black election worker Shaye Moss to “be glad it's 2020 and not 1920,” when white supremacists regularly lynched Black Americans for even trying to vote. These Trumpists suffered neither from a lack of information about the history of white supremacy nor incivility. Instead, the problem lies in the (uncivil) way they leverage nostalgia for a more overtly racist past to undermine Black political participation and, at the behest of Republican leaders, to hijack and transform the state into one that excludes and attacks everyone else.

So what does all this mean for us?

First, it means that we need to understand that, both structurally and ideologically, the protofascism of the Jim Crow era never left us. Rather, it has become the centerpiece of Republican ideology to such an extent that the 2022 Senate GOP election platform repeats fascist ideas and mythologies nearly verbatim. It is an alarming text and indicates the dire situation we now face.

Second, it is absolutely crucial that we understand the way these seemingly-unrelated laws and tactics are part of a totalizing program. If we fail to do so, we not only miss the scope of the fascist project but also Republicans’ substantial progress in bringing it to fruition. Since 2020, Republicans have worked overtime to limit the protections of the state to those who adhere to racist, sexist, classist, and fundamentalist hierarchies of the “great again” fascist nostalgia. A vast network of suppressionist laws, structures, and tactics, then, is already in place.

Third, we must use the state to destroy this fascist movement before it’s too late. That means, for example, prosecuting immediately the Republicans who planned and helped carry out the January 6th Insurrection. It means removing from Congress those who continue to promote the Big Lie and taking steps to prevent fascist propaganda networks from spreading lies and conspiracy theories. Failing to take these steps against the brazen fascism of the Republican Party means allowing them to continue plotting coup attempts and working towards a single-party state, plotting that led directly to a century of explicitly white supremacist rule in the wake of Reconstruction.

Going forward, I will use this space to engage 1) important antifascist thinkers from W.E.B. Du Bois, Aimé Césaire, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone Weil to Angela Davis, James Boggs, and Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), 2) the history and growing threat of fascist organizing in the U.S. and 3) ways we can circumvent or make inoperable the systems of exploitation that Republican fascists hope to control and build towards survival, liberation, and empowerment. While the situation we confront is indeed dire, I believe that we can sabotage fascist systems of power and, in solidarity with one another, seize for ourselves and our communities a more just and livable future.