What Is Fascism If Not Colonial White Supremacy Persevering?

Fascism grows out of colonialism. Stopping fascism means embracing anti-imperialism.

A little more than seventy years ago, the renowned Black intellectual and anti-colonial agitator Aimé Césaire observed that the horrors of fascism were nothing more than an application of colonialism on Europeans. “Before they were its victims,” he wrote, Europeans “were its accomplices… they shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples… they have cultivated that Nazism, [and] they are responsible for it.” Césaire’s analysis of fascism offered readers a withering indictment of “the barbarism of Western Europe” in Discourse on Colonialism, which became a staple of postcolonial thought, helping to inspire revolutionaries across the Global South to rise up against colonial regimes.

Last week, I explained “Why I Use The F Word (And You Should Too).” In response, some readers raised important questions about the relationship between our country’s racist history and the fascist renaissance advanced by today’s Republican Party. By taking a close look at Césaire, I hope to help answer some of those questions.

The short version is that I think Césaire and the Black radicals of his era got it right: fascism is a product of colonial white supremacy.

“Europe is responsible before the human community for the highest heap of corpses in history.”

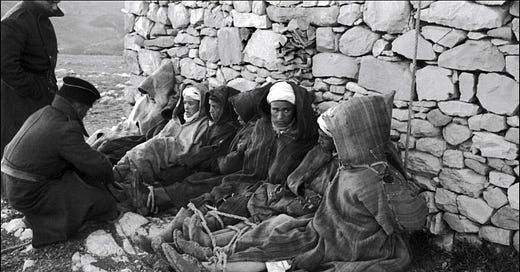

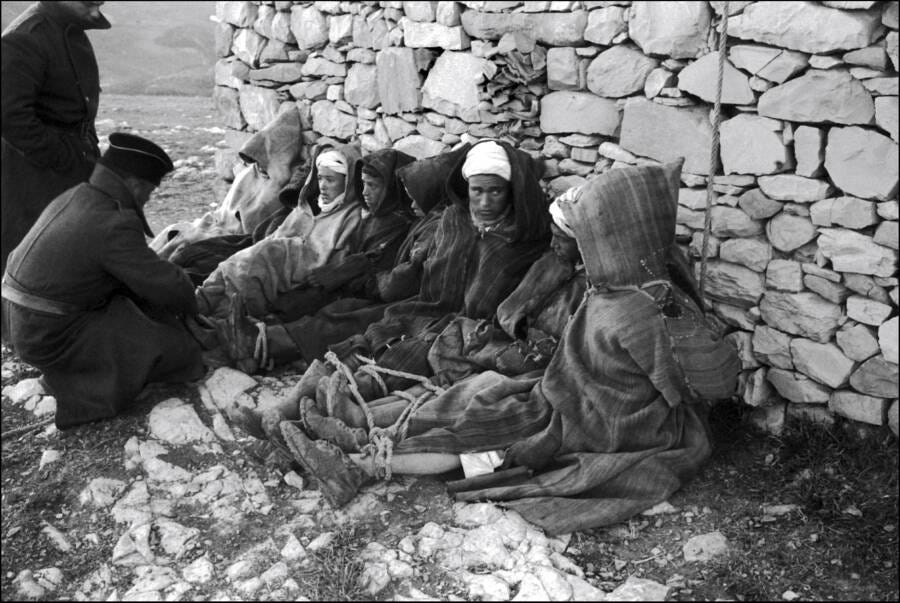

Césaire did not mince words in Discourse on Colonialism. He described colonialism as nothing less than a torture-for-profit scheme. While colonial officials “dazzle me with the tonnage of cotton or cocoa that has been exported,” Césaire wrote, the true cost of these resources was paid in the blood of colonized peoples. These same colonial officials, so excited about soaring profits, demanded to “have some heads cut off” or “a whole barrelful of ears collected, pair by pair” to terrorize locals into submission. European colonial regimes cared not for human rights or “civilization,” but for plunder—for profit and power for the imperial regime at the expense of its colonial subjects.

For Césaire, the European fascist regimes of the 1930s weren’t some weird aberration—a glitch in an otherwise humane “western” world. Instead, he saw these fascist parties and regimes as extensions of colonial systems of domination. While that might be an initially surprising argument for some readers, it makes a good deal of sense. Although colonial regimes claimed to be forces of civilization, they knew that they were torturing colonized peoples for profit. They gorged themselves on the fruits of colonial genocides and became intoxicated and degraded in the process. Césaire explains:

Each time a head is cut off or an eye put out in Vietnam and in France they accept the fact, each time a little girl is raped and in France they accept the fact, each time a Madagascan is tortured and in France they accept the fact, civilization acquires another dead weight, a universal regression takes place, a gangrene sets in, a center of infection begins to spread.

The center of this infection? Europe.

The act of colonizing, in Césaire’s reckoning, forced the French, the British, the Germans, the Italians, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the Belgians, the Americans, etc. to accept and embrace systems of genocide as their own. By participating in these colonial regimes, Europeans degraded and dehumanized themselves (an important topic I’ll come back to in greater detail in a future post) by becoming complicit in mutilation, plunder, and genocide.

Césaire observes a system of colonization with remarkable similarities to genocidal fascist regimes. He sees in both a system of racist and nationalist mythmaking that dehumanizes the colonized and promotes 1) regimes of violence, 2) systems of theft, and 3) complete political subordination. “Between colonizer and colonized,” he wrote, “there is room only for forced labor, intimidation, pressure, the police, taxation, theft, rape, compulsory crops, contempt, mistrust, arrogance, self-complacency, swinishness, brainless elites, degraded masses.” For Césaire, the difference between fascism and colonialism, then, is not ideological or even material but spatial. We call these systems colonialism when the rich and powerful use them in “undeveloped” countries and fascism when elites use these same tactics in “developed” countries like, say, France, Germany, or the United States.

So if these are fundamentally similar systems of suppression, theft, and violence, why does our public discourse treat fascism as uniquely bad, in a category all of its own? Césaire tells us, and it’s not pretty: “What [Europeans] cannot forgive Hitler for is not the crime in itself… it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘n*****s’ of Africa.” The way that we view the world in “western” countries, Césaire suggests, is overwhelmingly shaped by colonial history and ideology.

Our systems of information, ethics, and governance are intertwined with colonialism. We’re taught to accept atrocities in “undeveloped” countries, even those committed by our military, as part of some natural order of things while at the same time we champion our commitment to democracy, self-governance, and human rights. “And that is the great thing I hold against pseudo-humanism” Césaire fumed, “that for too long it has diminished the rights of man, that its concept of those rights has been—and still is—narrow and fragmentary, incomplete and biased and, all things considered, sordidly racist.” This colonial “humanism” is a nationalist ideology of mass death—a rotten corpse masquerading as lady liberty.

Is fascism ultimately the practice of colonialism in “developed” countries and on “civilized” populations?

Yes.

While it’s possible to approach Césaire as a “product of his time” and to dismiss his critiques as dated, I think this would be a mistake. Césaire wrote just after the fascist genocides of the Second World War and amid a raging worldwide anticolonial conflict against the forces of imperialism. In fact, he experienced the overlap between these systems during his time under Vichy rule in colonial Martinique. Vichy, remember, was the fascist French puppet regime created as part of the French surrender to Nazi forces in 1940.

In Césaire, we have an opportunity to examine the ideologies and systems of power that created the world we inherit.

As with the British and other imperial powers, the U.S. has waged constant wars of plunder against weaker states since 1898 (and earlier too in the Mexican-American War and genocidal campaigns against Indigenous nations). While colonial systems are “exploited by the few—the self-same few who wrung dollars out of blood in the war,” Gen. Smedley Butler observed in War is a Racket, “the general public shoulders the bill.” Butler denounced what today we would call the military industrial complex, a system of plunder and profiteering in which wealthy elites benefit from the “creative destruction” of war. The brazen profiteering of politicians and their wealthy and well-connected friends weakens trust in institutions, making democracies like our own more susceptible to authoritarianism.

Truthfully, this relationship between colonialism and fascism isn’t even that complicated. It’s just much easier to believe the nationalist lie that the U.S. is a beacon of freedom than it is to accept that this country stole regularly and remorselessly from vulnerable communities across the globe, from the Deep South to the Global South. But these endless colonial wars against vulnerable communities further destabilize those regions, promoting manufactured migrant “crises” while straining public coffers, both of which contribute to fascist politics.

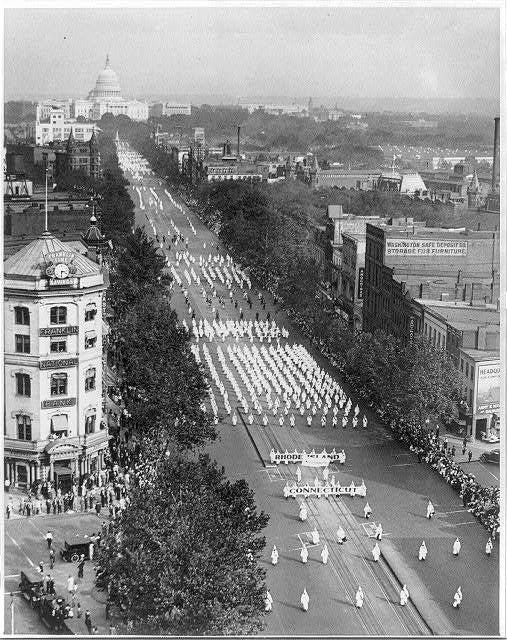

We don’t have to look far to see the way colonial regimes create instability and promote fascist politics. As Black Americans fled the lynching, massacres, voter suppression, and wage theft of the Jim Crow South in what became known as the Great Migration, white Americans responded by nationalizing the Ku Klux Klan and racist housing, education, and employment practices.

So what does this mean for us?

Césaire helps us understand how colonialism contributes to fascism. As we confront a brazenly fascist Republican Party, Césaire gives us a chance to understand how our country’s longstanding commitment to white supremacy at home and abroad led to this point. He also suggests the way forward:

The problem is not to make a utopian and sterile attempt to repeat the past, but to go beyond. It is not a dead society that we want to revive. We leave that to those who go in for exoticism. Nor is it the present colonial society that we wish to prolong, the most putrid carrion that ever rotted under the sun. It is a new society that we must create with the help of all our brother slaves, a society rich with all the productive power of modern times, warm with all the fraternity of olden days.

For Césaire and countless other Black radical thinkers, organizers, and revolutionaries, we can only move forward towards peace, stability, and prosperity in solidarity with one another. This means 1) pressuring institutions to meet our collective needs, 2) undermining and sabotaging colonial systems of theft and violence, and 3) creating new ways of distributing resources and democratizing power.

Above all and most urgently, it means that we must prevent fascists from cementing their power by taking over the state.