Torchbearers of Democracy

Burning down an unjust system can help us finally achieve justice and equality.

One of the questions I get a lot is how we fight back against fascist systems of oppression. While no single answer or tactic can meet our collective needs, I find it useful to look to historical revolutionary thinkers and movements for inspiration. The ways they analyzed systems of power and took enormous risks to upend them offer important lessons for us in the present. Below I look at two revolutionary moments, the Haitian Revolution of the 1790s and the Urban Rebellions of the 1960s to think through how we should respond to fascist organizing and state violence today.

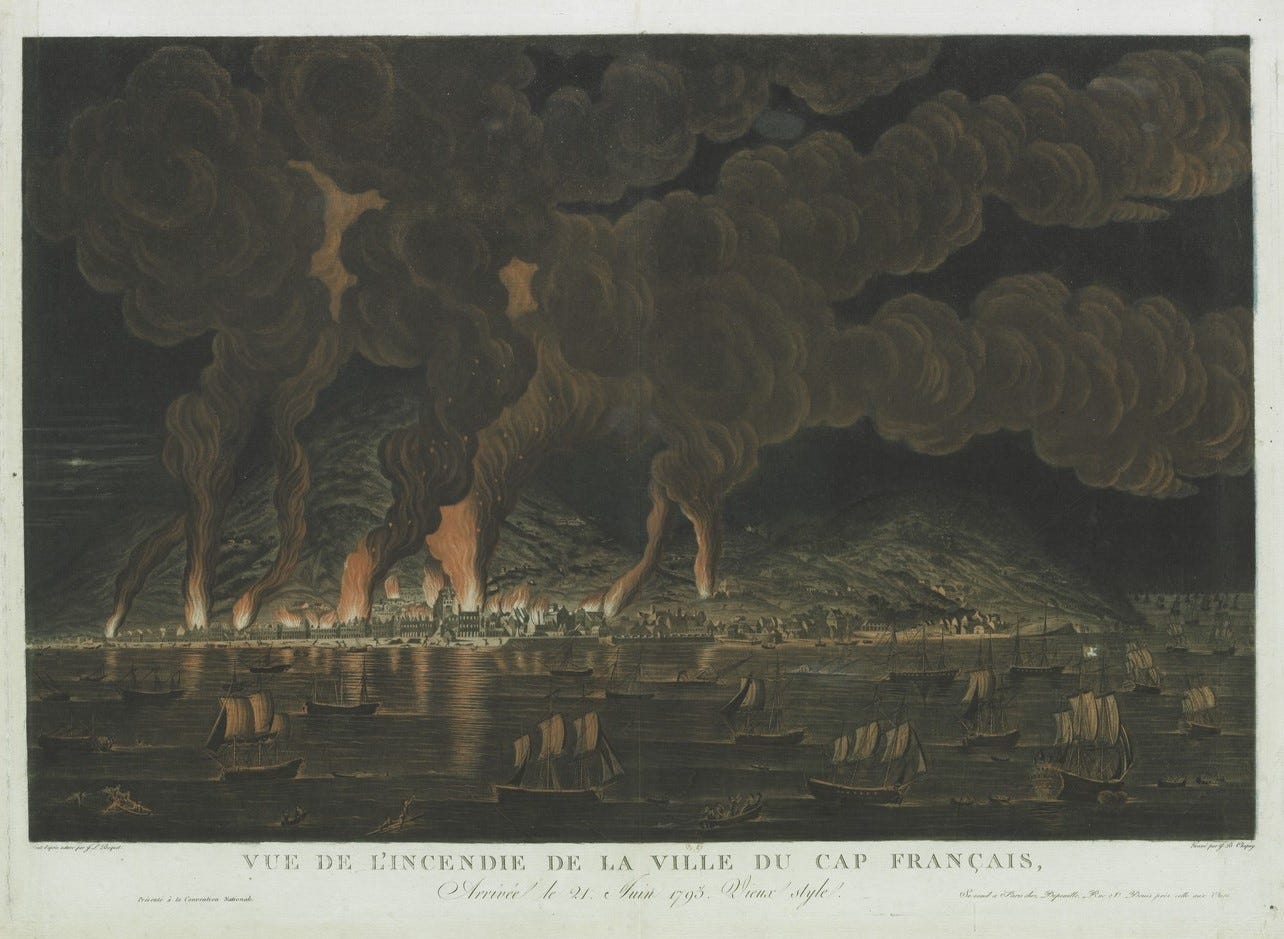

Beginning in August 1791, Black revolutionaries torched the plantation landscape. They set fire to sugar mills, cane fields, and plantation estates, making an intricate white supremacist system of torture, profit, and power totally unusable. The flames they spread launched the Haitian Revolution, an antislavery rebellion that would defeat the French, Spanish, and British empires before establishing the first antislavery state in the Western Hemisphere.

Although historians, teachers, and organizers have done excellent work telling this story in recent years, it is one that I find consistently surprises even highly informed audiences. That’s no accident. Those in power went to extraordinary lengths to suppress news of the Haitian Revolution and whitewash the history of the revolt. They understood that a successful slave revolt undermined the racist mythologies they used to justify the plantation economy and the world of consumer goods it created. In many respects, their (successful) efforts to whitewash the Haitian Revolution in the early 1800s represented the first anti-“CRT” campaign, an attempt to make the world safe for white supremacy.

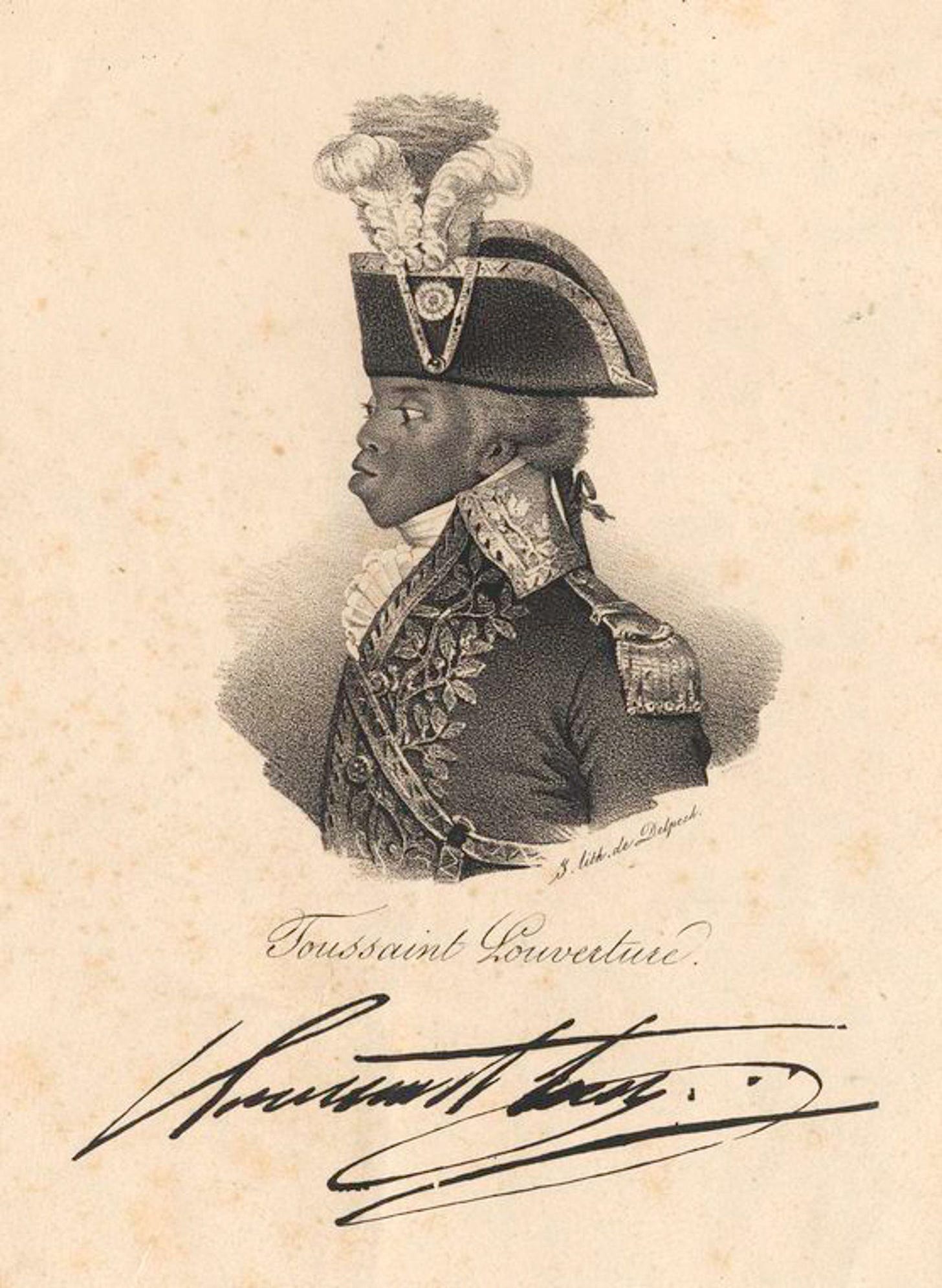

While white elites did everything in their power to cover up the revolution and its impact, they did get one thing right: knowledge of the Haitian Revolution did indeed spread the flames of Black revolution far beyond the shores of Haiti. As historians have shown, we can better understand events like Second Maroon War of 1795 in Jamaica, the multicultural German Coast Rebellion of 1811 in Louisiana, and the Black and Indigenous defense of Negro Fort in 1816 as part of this larger transnational Black revolutionary movement. Abolitionists in the U.S. even found ideological and tactical inspiration in reports of the revolution and its most famous leader, Toussaint Louverture. The abolitionist raid on Harpers Ferry, for example, which has long been seen as a catalyst for secession and the Civil War, grew from a close reading of Louverture and the lessons of the Haitian Revolution.

In a very real sense, the white supremacist slaveocracy—the Black engine of capitalism—teetered on the brink of human liberation, dragged kicking and screaming towards equality by the organizing of abolitionist torchbearers.

From the vantage point of the present, of course, we know that these efforts failed to topple white supremacist systems of profit and power. But they reveal two important lessons: 1) revolutionary knowledge inspires revolutionary action and 2) when we approach the systems of power as gears in a machine, it becomes possible to consider how to break that machine and liberate those upon whom it feeds.

As we come to terms with the implications of a fascist Republican Party and its attempt to corrupt and capture our already-racist institutions, engaging this Black radical tradition offers us the tools and vocabulary to seize a just and equitable future.

Torchbearers

One of the central lessons of the Haitian Revolution and subsequent Black liberationist thought is that existing institutions were created to serve white elite interests exclusively, at the expense of everyone else. Enslaved people in Haiti didn’t choose to revolt because they had too much time on their hands or, as enslaver Bryan Edwards argued in 1797, because white abolitionists put the idea of freedom into their heads. They risked life and limb to fight for their freedom because, as Jean-Jacques Dessalines wrote in the Haitian Declaration of Independence, French enslavers were “barbarians who have bloodied our land for two centuries.” As Dessalines saw it, the Haitian Revolution wasn’t an act of violence, but an attempt to end an existing genocidal torture-for-profit scheme.

James Boggs, along with other important civil rights era revolutionaries, made much the same argument about the white supremacist design of the U.S. state. He wrote that “after a system has existed for this long, it has to be judged by what it is & what it has been, not by the alleged hopes or faiths of its founders or supporters.” Or as James Baldwin observed a year earlier, the government exists “to keep the Negro in his place and to protect white business interests, and they have no other function.” White elites themselves make abolitionist revolution necessary by writing their own racist depravity into law and weaving it into everyday practice.

For the Haitian Revolutionaries, acting as torchbearers of liberation meant, first and foremost, setting fire to the products of their oppression. Historian C.L.R. James explained:

Each slave gang murdered its masters and burnt the plantation to the ground. The slaves destroyed tirelessly. They knew that as long as those plantations stood, their lot would be to labor on them until they dropped.

In the tactics of the revolutionaries, James identified a sophisticated analysis of the systems of profit and power created by French enslavers. By destroying the sites of their enslavement and the fruits of their stolen labor, the antislavery Black revolutionaries understood that they were quite literally burning down the reason for the regime’s existence. Only from the ashes of such a system, they doubtless reasoned, could liberation be realized.

Boggs likewise denounced the government erected by centuries of white supremacist rule in the U.S. White Americans celebrated equality and democracy, Boggs wrote, but “Black people have been living under fascism right beside them.” He “question[ed] whether a system which has existed under uniquely favorable conditions for so long and has kept a whole race in subjugation is itself worth maintaining.” At this point, we know what the U.S. is—we know what it does, who it benefits and at whose expense. Carrying the torch of democracy and equality means, as Boggs suggests, knowing what needs to be burned and why.

Malcolm X pointed to the same fundamental (white) unwillingness to apply American laws, customs, “norms,” or the “American Dream” to Black Americans. “Concerning anything in this society involved in helping Negroes,” he thundered, “the federal government shows an inability to function… it can function in South Vietnam, in the Congo, in Berlin and in other places where it has no business. But it can’t function in Mississippi.” The U.S. could wage wars of empire, maintain decades-long occupations, and create elaborate systems of surveillance and sabotage to fight its alleged enemies abroad, but refused to protect the rights of its (Black) citizens within its own borders. Can justice ever be achieved under such conditions? Is such a system of violence and fraud worth “reforming”?

As with their successors in the Urban Rebellions of the 1960s, Haitian Revolutionaries applied this torchbearer’s lesson well, making the unjust system of plantation slavery impossible to maintain. Despite the destruction of the Haitian Revolution, James asserts that “on the whole, they never approached in their tortures the savageries to which they themselves had been subjected.” James echoed Dessalines on this point, who reminded his audience in the Haitian Declaration of Independence that “your spouses, your husbands, your brothers, your sisters” were “the prey of these [French] vultures.” The regime was already violent—that was the very reason it existed. The revolution sought simply to end that violence.

Would it have been more “humane” to beg French enslavers for mercy? To point out their “hypocrisy” and hope to somehow inspire guilt in such cultured and refined genocidal torturers? Even this benign and restrained activism had been too much for enslaver Bryan Edwards who, remember, denounced white abolitionists as terrorists for even talking about emancipation. This is, by the way, exactly the argument that Republicans make today about saying the phrase Black Lives Matter.

Whether in Cap-Haïtien or Washington, D.C., those in power remind us that politely requesting an end to existing systems of violence 1) will never be sufficient on its own and 2) will consistently be denounced as violence by those in power wielding actual violence. Haitian revolutionaries took up the torch of freedom because they carefully analyzed the system of torment and plunder that entrapped them—because they knew that oppression is not another step on the path to liberation but a military checkpoint blocking the way that must be totally destroyed and its ashes scattered.

Democracy

During the Haitian Revolution, “Black slaves, singing the Ça Ira and the Marseillaise and dressed in the colors of the [French] Republic,” fought back against the forces of slavery. Under Toussaint Louverture, Haitian revolutionaries remained loyal to the French Republic and passed a new constitution in 1801 abolishing slavery and mandating equality before the law. Article three of the new constitution stated that “there cannot exist slaves on this territory, servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French.” French colonial officials might have avoided further bloodshed then, as at the beginning of the revolution, by simply accepting Black freedom and their own revolutionary ideals. Yet their love of profit and power outweighed their commitment to Black rights. They would allow no happy ending in Haiti.

Despite their egalitarian rhetoric and the Haitian commitment to the French Republic, colonial officials tried to reinstitute slavery on the island. Dessalines alluded to precisely this when he reminded Haitians that they had become “victims of our [own] credulity and indulgence for 14 years; defeated not by French armies, but by the pathetic eloquence of their agents' proclamations.” Indeed, the very French state that had issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man kidnapped Toussaint Louverture, carried out mass executions, and deployed “man eating dogs” in hopes of restoring slavery on the island.

The prospect of re-enslavement that Haitian revolutionaries refused to accept reminds me a great deal of Malcolm X’s famous demand for Black equality “by any means necessary.” While it is remembered by those in power as a threat of violence, it was the racist state that refused to protect Black civil rights that made armed self defense necessary. That’s because actual democracy is incompatible with racial oppression. It was the enslavers who created the need to revolt in Haiti as it was racist white elites—those with actual institutional power—who created the Urban Rebellions that they so indignantly denounced.

Boggs identified this fundamental incompatibility of democracy and white supremacy as the basis for action, concluding that “the Black revolution must create a kind of society which goes far beyond any that have been achieved by the revolutions of the past.” For Boggs, this meant that the benefits of technological innovation—“automation and cybernation”—must be distributed evenly to improve the lives of everyone in society. Instead, the elites of his day advocated for work as the fundamental organizing feature of society, criminalizing, ostracizing, and starving those excluded from work. They created an explicitly carceral capitalism—through which they continue to maintain power in a deeply unequal and unstable society—a system not all that different from what we see today in the form of “longtermism” and other ideologies of racist convenience.

While Boggs was reasonably skeptical of American democracy given its abysmal track record for Black Americans, he reasoned that a torchbearer’s movement could create meaningful equality.

The simultaneous rebellion of the Black masses in major cities would create a mass disruption of production, transportation, communications, and all political and social institutions greater than it created by the strikes of the 1930s and comparable to those created by the recent general strike in France. This would be the effect of spontaneous rebellion. On a planned scale it could result in the complete control of the cities, and therefore of the heart of the nation.

Although this type of movement might seem “dramatic” or “extreme” in the eyes of the powerful, it is the existing unjust system that makes this sort of dramatic action necessary. Those in power could, in fact, make the grassroots collective action Boggs imagines unnecessary by embracing actual democracy and equality. But of course, that would require them to give up profit and power, something they have never willingly done.

I’ll sketch out more of the grassroots democracy response to Republican fascism next week. For now, it’s worth considering what thinkers like Toussaint and Dessalines, Boggs and Malcolm X reveal: that an actual nonviolence requires that we sabotage existing systems of profit and plunder.

Note: I had a wonderful discussion last week with Sharif El-Mekki (@selmekki) and Chris Stewart (@citizenstewart) on their #FreedomFriday podcast hosted by Ed Post (@edu_post). If you’re interested in thinking through the implications of the Haitian Revolution for today, you may want to check it out. And many thanks, Sharif and Chris, for having me!