What Christian Nationalism Looked Like in Practice

If America was indeed a “Christian nation”—there is nothing less desirable or great than making it one again.

****Below is a passage from my recent TIME article on white Christian nationalism. You can read the full version here.****

When speaking recently at an evangelical town hall led by Lance Wallnau, J.D. Vance explained that his goal of dramatically restricting U.S. immigration is grounded in the "Christian idea that you owe the strongest duty to your family." His comments and appearance with the man who has in the past described himself as a Christian nationalist engages a set of beliefs common in the Republican Party and among a slice of the electorate: that America was founded as a white “Christian nation” based on God’s law as expressed in the Christian Bible.

Indeed, at a meeting of conservative Christians in February, Trump appeared to gesture toward that idea, with his promise that, “With your help and God’s grace, the great revival of America begins on November 5th.”

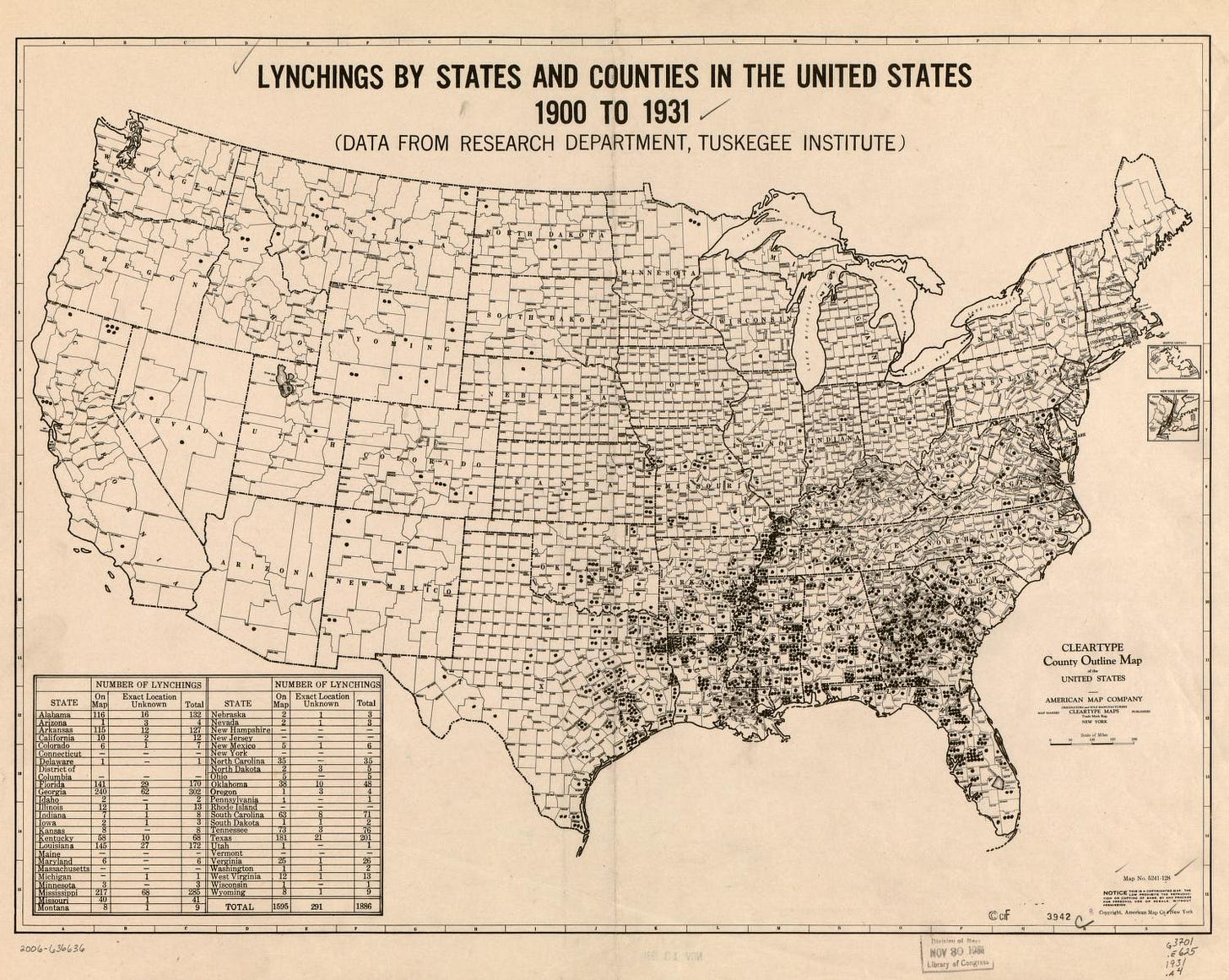

Despite this rhetoric, the U.S. was not founded as a “Christian nation,” an idea the Trump campaign rhetoric supports. Historically, laws at the state and national level during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, meant to counter waves of Catholic and Jewish migration and to suppress Black suffrage, sought to wed Protestant Christianity and white supremacy to the state. Such attempts led to widespread suffering, poverty, and death, especially for racial and religious minorities targeted as "immoral" by Christian activists.

Today we remember the product of this Christian nationalist movement as Jim Crow, the brutal and repressive set of laws and practices that structured American life from the 1890s through the 1960s. The terrible suffering they created shows that—if America was indeed a “Christian nation”—there is nothing less desirable or great than making it one again.

Following the abolition of slavery after the Civil War, white evangelicals embarked on a reform campaign, aiming to purge society of what they viewed as religious and social ills. They founded powerful advocacy organizations like the American Economic Association and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union to, in the words of one reformer, “bring to pass here a kingdom of righteousness.”

Advocacy organizations like these sought to pass laws beginning in the 1890s criminalizing drinking, swearing, and loitering while working to restrict integrated spaces, immigration, voting, and reproductive rights. While these laws and organizations varied based on locality—the Asiatic Exclusion League in San Francisco targeted Asian Americans, for instance—the legal and organizational framework they created promoting white Christian power, at the expense of other groups, was national in scope.

Frances Willard was among the most prominent of these Christian reformers and longtime president of the national Women’s Christian Temperance Union. A northern daughter of abolitionists, her biographer noted that “she never let go of her belief that a healthy democracy required all its citizens to conform to a singular standard of morality.”

To achieve that end, Willard worked to ban the sale and consumption of alcohol while supporting the suppression of groups she found morally unfit. For example, during the Mississippi Constitution of 1890, convened specifically to formally disenfranchise Black voters, Willard touted its work as an example of moral reform and called for it to grant limited voting rights to white women while disenfranchising Black men. The convention failed to give the vote to women, but it used poll taxes and felon disenfranchisement to restrict Black suffrage. Often considered to be one of the foundational texts of Jim Crow, the new constitution framed its work as seeking to harmonize civic life with the divine, with the text “invoking His blessing on our work.”

Read the full version here.