The Republican Party Is Unpopular And It Knows It. That’s Dangerous.

Growing opposition to Republican policies disincentivizes the GOP’s already waning commitment to democracy and increases the risk of racist mass violence.

***This essay first appeared in and is reprinted here with the permission of the Bucks County Beacon.***

We all heard the predictions. A red wave. A backlash. A reckoning. The 2022 midterm elections were supposed to be all that and more, and yet, Democrats won statewide elections handily in competitive races despite the very real bread and butter issues that so many Americans face, precisely because the Republican Party is the actual cause of these problems. From their opposition to welfare, healthcare, childcare, and social security to their support for corporate tax breaks and the oil and natural gas industry, the GOP has long and vehemently opposed policies designed to help working people. I mean, they even sabotaged the U.S. Postal Service not once, but twice.

These Republican policies are deeply unpopular and have been for quite some time. In the midterm election, only aggressive gerrymandering and voter suppression in states like Ohio, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Texas, and Florida have preserved a glimmer of electoral hope for Republicans.

The problem we increasingly face is that Republican policies and tactics are genuinely unpopular. And I mean this sincerely—that unpopularity represents a serious problem because it further disincentivizes Republican commitment to democracy and increases the risk of racist mass violence.

In the days since the election, countless pundits concluded that the extremism of the Republican Party hurt its electoral prospects. Emblematic of this coverage, Jonathan Weissman reported “recriminations” within the GOP over the potential causes of the midterm defeats: “poor candidates, an overheated message or the electoral anchor that appeared to be dragging the G.O.P. down, former President Donald J. Trump.” The list is perhaps more revealing than Weissman realized — each of these potential “causes” of the GOP’s poor election returns are actually central to the Republican Party itself. It’s who they are. A prime example from Weissman’s own analysis: the alleged “moderate” and implicitly “electable” Republican, Mitt Romney, supports exactly this same set of policies — cutting Social Security and Medicare, for example — but simply employs a more “respectable” tone. Like, doesn’t anyone remember Paul Ryan?

Neither Romney nor his allegedly more “overheated” (really, that’s Weissman’s actual euphemism for ethnonationalism) Republican candidates are outliers in this regard, at least not since Nixon’s race-baiting 1968 Southern Strategy campaign. In fact, white conservatives have made undermining public services the centerpiece of their modern organizing since, well, the 1954 Brown ruling and the massive political realignment that the mere prospect of integration initiated. Conservatives have spent the last sixty-plus years chipping away at the legal framework of civil rights, a process that the Roberts Court has accelerated dramatically from gutting the Voting Rights Act in Shelby (2013) and Brnovich (2021) rulings while giving tacit approval to gerrymandering, a tactic overwhelmingly used by Republicans to retain power over the objections of voters.

Politically, white conservatives have mobilized against civil rights and equality since the moment of emancipation, passing and implementing a number restrictions from vagrancy laws and convict leasing to segregated housing, education, and employment opportunities to undermine equality. The success of these tactics allowed white conservatives to support public services, for the most part at least, with the understanding that they would be denied to Black and Indigenous Americans and to migrants. A New Deal is fine, for example, so long as its beneficiaries are white.

Often, white conservative policy restrictions have come in direct response to movements and laws designed to protect Black civil rights. In the wake of the Brown ruling, for instance, white conservatives created “segregation academies” which, along with redistricting and white flight, were designed to prevent school desegregation. As I wrote in the Washington Post, the white flight suburbs also put a strain on infrastructure and, in Baton Rouge, contributed to chronic flooding.

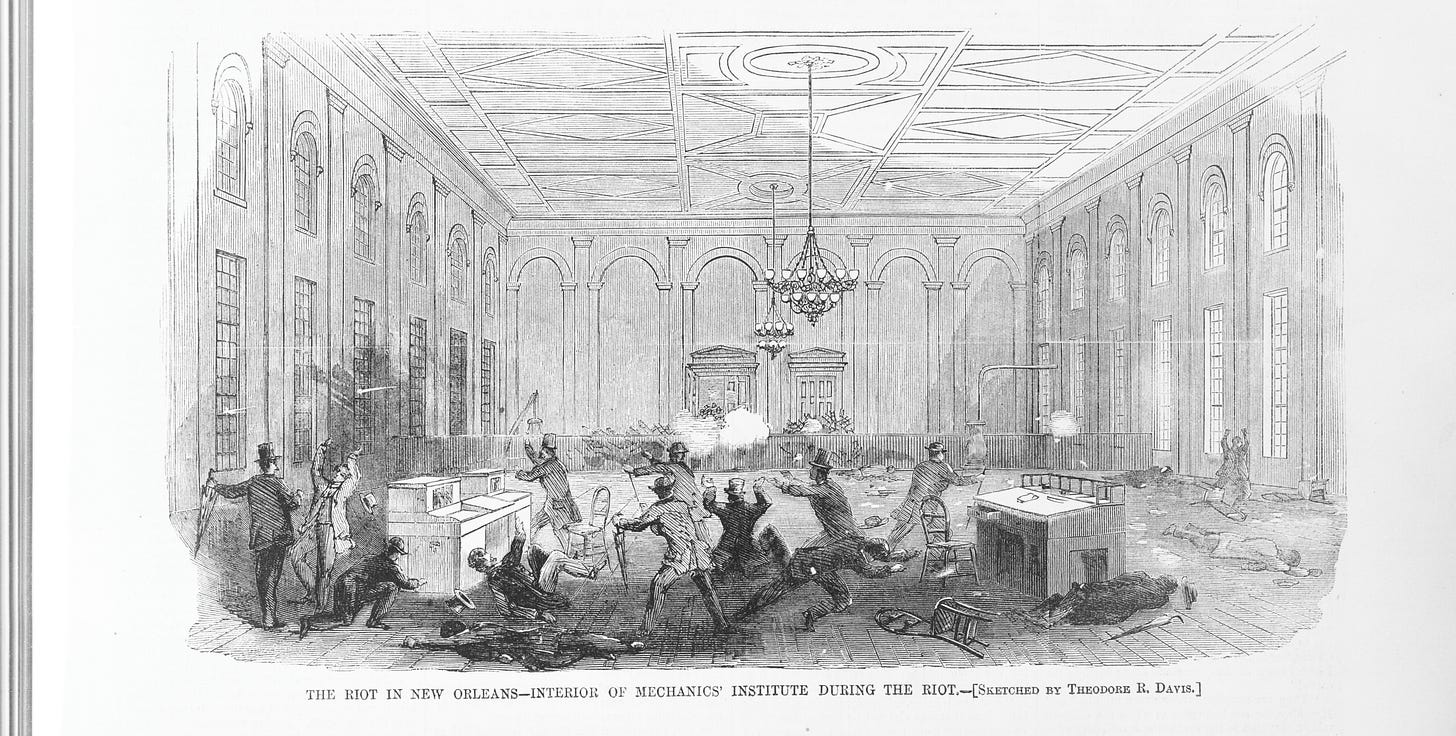

Those white conservative political movements opposed to civil rights and equality have all too often included racist mass violence. When an interracial coalition of voting rights activists demanded Black enfranchisement in at the Mechanics’ Institute in New Orleans on July 30, 1866 — just a year after emancipation — white police and firemen stormed their suffrage convention and massacred participants with the help of a white mob. While that event rarely makes it into history classrooms — I’m working on a documentary right now to help correct that — it was hardly an outlier among white conservatives’ responses to movements for civil rights and equality. From the 1874 Liberty Place Coup and the Wilmington Coup in 1898 to the 1917 St. Louis Massacre and the Tulsa Massacre in 1921, white conservatism has long exhibited the mantra that “if you can’t beat ‘em, kill ‘em.”

We see just such a movement within today’s white conservative Republican Party, whose rhetoric just inspired yet another mass violence event targeting LGBTQ patrons at Club Q in Colorado Springs, something that should come as no surprise in the wake of the El Paso and Buffalo shootings. It is a feature of the so-called “culture wars” turn in the GOP, which for those versed in U.S. history, represents less of a turn than a return to a politics of explicit state repression and vigilantism, one in which was the defining feature of American politics for most of our history.

Writing amid the blatant refusal of white conservatives to implement the reforms of the civil rights era, activist and theorist James Boggs wrote that “after a system has existed for this long, it has to be judged by what it is and what it has been, not by the alleged hopes or faiths of its founders or supporters.” Boggs critiqued the system of in-name-only democracy celebrated by white conservatives, but we might ask the same of the Republican Party today.

There comes a point where we have to recognize the Republican Party for what it is rather than for what we wish it to be. What it is, unfortunately, is an institution committed to a militant white nostalgia that poses a threat to American democracy both through electoral means but also through extralegal measures, as the January 6th Insurrection and the persistent and ongoing election denialism have made all too clear.

What that means, sadly, is that we can’t rest in the conviction that we positioned ourselves well for a victory in the next election. Indeed, we operate in a system in which one political party seems to have given up on democracy entirely, one in which each passing election may well be our last. The Republican Party is unpopular. It knows it. That really does represent a massive problem, one with potentially devastating outcomes for millions of us.

***Love and solidarity to our LGBTQ brothers, sisters, cousins, queers, and queens.***

NOTE: Many thanks to reader Ron Lusk, who pointed out a missing word in the initial version of this post.