Incarceration, Abolition, and the Future of Work

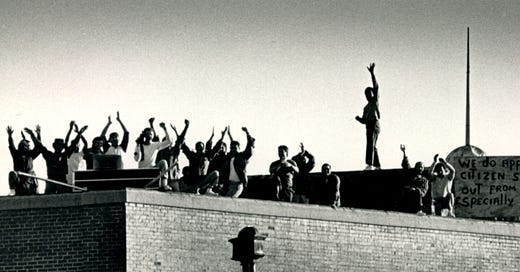

Like our other systems, policing and prisons help to manage and reinforce a particular vision of work, one that criminalizes and commodifies the very poverty produced by racial capitalism.

I recently spoke at an academic conference on studies of incarceration and their relationship to abolition and wanted to share my opening remarks here. While I don’t normally share these, I think this gives a decent overview of the field and its relationship to organizing towards liberation that I hope some readers will find useful.

First I want to thank everyone for being here and for my fellow panelists for this collaboration, which I hope will spark a fruitful conversation this morning.

I’m very interested in Black grassroots radical politics during the nineteenth and early 20th centuries and how this intellectual and organizing work reflects a coherent ideology and revolutionary praxis distinct from, let’s say, schools of thought, hegemonies, or stageist analyses. The Black radicals of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave damning assessments of the state based on a sophisticated analysis of the relationship between wealth, power, and oppression. These logics informed and inspired organizing efforts in collectivism, in what I call a utopian praxis, and in antiracist, radical feminist, and democratic imaginaries that remain deeply necessary today.

So lately I’ve been thinking much bigger picture about what carcerality means. While of course we’re talking about surveillance, policing, and prisons, for the Black radicals of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, understanding incarceration means analyzing the workplace. It means looking at foodways, at labor, at care work, and at the distribution of opportunity. Abolitionist thinkers like Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore have long made this point, but I think it remains one that we’re largely loath to apply to “Southern spaces” and 19th century places. That’s unfortunate because I think it keeps us from fully understanding these movements and the functional utopias they created in response to the very real dystopian landscapes of incarceration and deprivation.

In preparation for this session, we considered how our work challenges narratives around the carceral state and its development and this is such a good question, because I think if you asked most scholars about the origins of the carceral state, they might reasonably begin with federal policy embodied in, say, Nixon, Reagan, or Clinton (or Biden). Those of us in this discussion today, I think, would posit a different answer. While these men each represent key moments in the history and development of carcerality, particularly as a means of dealing with chronic poverty and unemployment, focusing on these points of very real horror drowns out the systems at work beneath the surface—it veils the way that mass incarceration represents less a rupture than an expression and evolution of existing systems.

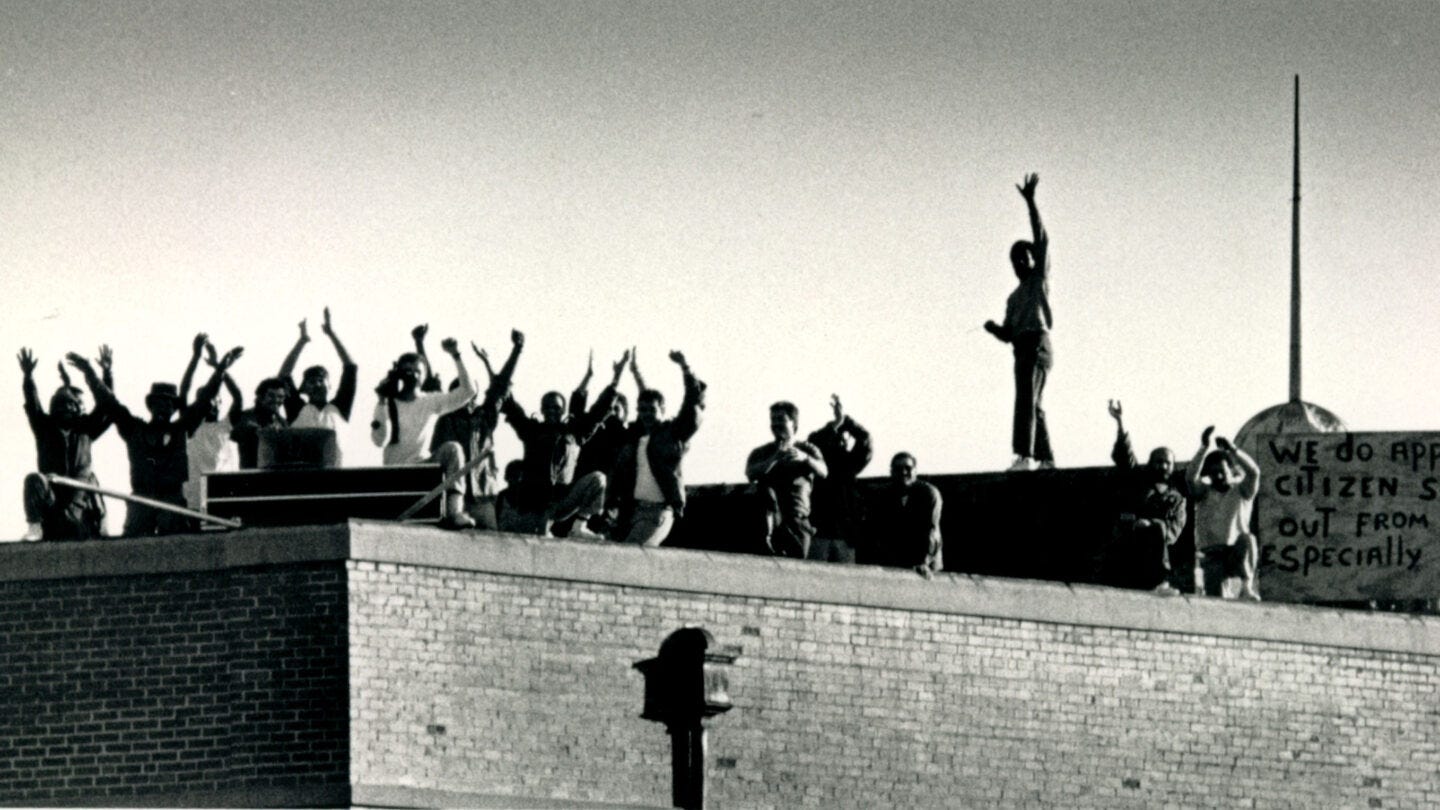

Studying incarceration, for me, means seeing policing and confinement as one expression of this larger system of racial capitalism alongside more everyday things like forced deprivation, speed-ups, subcontracting, and wage/price-fixing. It means, especially, looking at where these systems of bondage and deprivation coincide—where incarcerated workers share spaces, conditions, and labor with unbound persons nonetheless disciplined by the carceral state. We might look, for example, at the literally incarcerated workers who facilitate the production, processing, and preparation of food, but we might also look at how immigration policy functions as a sort of carceral net—what Mary Mendoza terms a “caging in”—binding undocumented workers and their families to unwaged, underwaged, and coerced labor.

So for me and many of the folks looking at what we might call the afterlives of slavery and Jim Crow, the bedrock of carceral systems lies less in particular modes of policing, specific types of punishment, or the number, square footage, and demographics of American prisons. Instead, we find it in racial capitalism and the various regimes of surveillance, coercion, labor, discipline, and deprivation that make racialized plunder into business as usual.

Some of my recent and ongoing projects illustrate what I mean by changing how we frame incarceration. I’m writing two academic articles right now: one on white abolitionism as elite capture and another on what I term Black radicals’ utopian praxis—what together we might think of as analyses of liberal “prison reform” and radical abolition. “White abolition” consistently repurposed abolitionist rhetoric to reproduce the race and class hierarchies of the plantation regime during the destruction of slavery—a counterrevolution both within and against the project of abolition. Black grassroots agrarian thinkers and organizers, on the other hand, demanded and occasionally won, if briefly, an entirely different system, one built upon radical democracy, collectivism, and universal rights. Taking a closer look at these divergent forms of “abolition,” I hope, will help denaturalize incarceration and show the ways that abolition has been historically sabotaged by elites in service of capitalism—in their pursuit of ever-greater profit and power.

A deeper dive into the radical imaginary of 19th century abolitionists and the maroon communities that informed them inspired a further set of projects on Mardi Gras as liberation: a forthcoming chapter and a standalone edited volume, tentatively titled “A People’s Mardi Gras.” The radicals of Mardi Gras across the Gulf South, while outside formal systems of power, inverted existing hierarchies, critiqued those in power, and celebrated a vision of community and collectivism antithetical to the carceral regime of the postemancipation state. As with “abolition,” the institutionalization of Mardi Gras and the capture of its symbols, rituals, and traditions has only hampered its liberatory potential. These projects tell the story of the competing commitments and ideologies that shaped how our society has understood and responded to the exploitation and expropriation of Black Americans. They reveal, for me, the difference and distance between reform and revolution and help carve out a path towards liberation.

We might also look at the issue of incarceration through the lens of critique—analyzing and ideally undoing existing systems of oppression. My forthcoming chapter on agrarian carceralities in The Civil War and the Summer of 2020 edited by Hilary Green and Andy Slap, does just this, asking essentially where the prison ended and the workplace began, whether employers, owners, managers, and “entrepreneurs” count as members of the judiciary. I think they do and, for what it’s worth, formerly enslaved people treated them this way. Their organizing and experiences ask us to consider whether abolition requires a transformation of work itself. Again, I think the inescapable answer is yes.

My recent chapter, “The Vampire’s Bacon” in Vegan Entanglements views the question of food work and incarceration as one involving nonhuman animals too. If dehumanization and commodification represent the primary vectors of racial capitalism for racialized and especially Black workers, does abolition necessarily involve a rejection of logics of commodification binding nonhuman animals? Once more, I suggest that while they vary in degrees of urgency—we rightly prioritize human over nonhuman wellbeing—these are questions that cannot be unbound from one another.

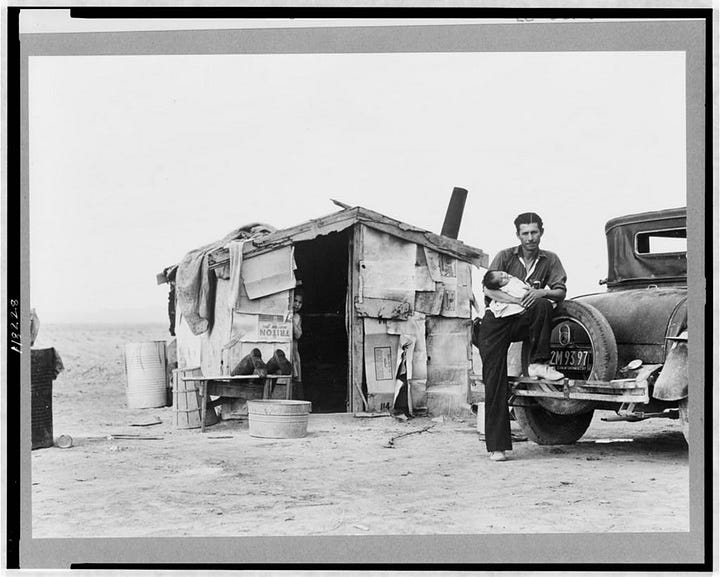

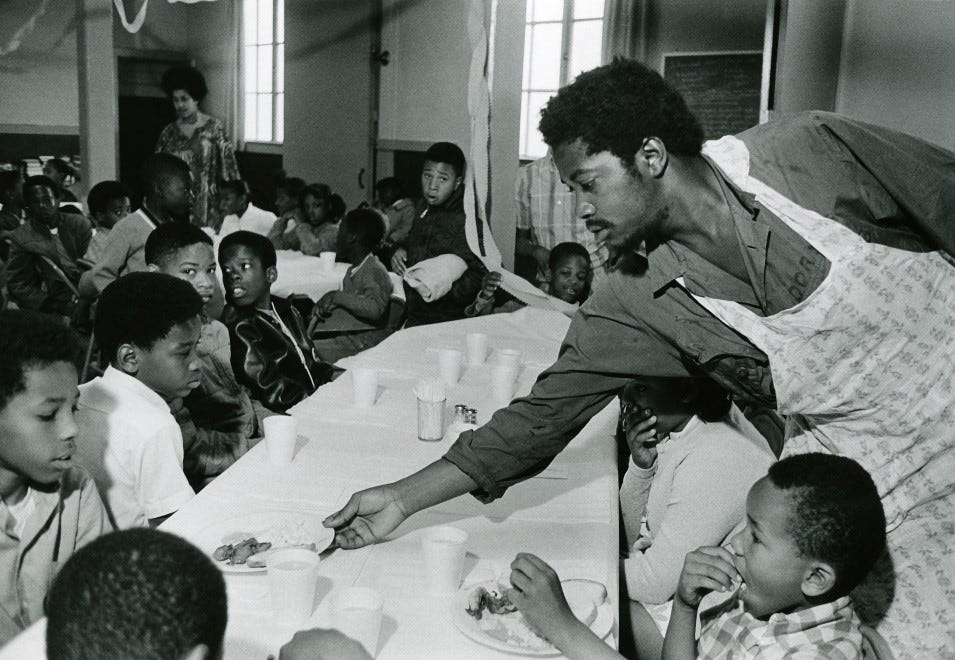

I hope that seems like a random assortment of projects because that’s sort of the point—abolition is multifaceted and complex, and asks us as thinkers and agitators to both critique existing systems and to imagine new ways of being. To that end, one thing we talk less about but that’s huge in the archive is food and food work. It’s not exactly an “undiscovered” or “forgotten” history or anything like that, but access to food—which means access both to survival and community—was and remains at the forefront of abolitionist organizing. Food sovereignty gives workers the opportunity to participate (or not) as equals in the wage economy. With food access comes power, autonomy, and self-determination, a fact that has never eluded grassroots radicals and organizers so much as it has some of us studying their work.

So as we look toward the future of carceral studies and abolitionist labor, as the recent Haymarket collection Abolition Feminisms does so beautifully, I think we must look at this space between life and lifelessness—between liberation and incarceration—as the scope of both the field and the struggle that it demands.