Fascism or Democracy: The Work Behind, the Work Ahead

If America’s greatness is its love of freedom, who held the firehoses in Birmingham? Who wielded clubs on Edmund Pettus Bridge?

***A version of this essay first appeared in and is reprinted here with the permission of the Clio and the Contemporary.***

The outcome of the recent election likely came as a shock to many of us. Donald Trump is so unqualified—a brazenly racist, sexist fraudster and serial sexual assaulter who tried to overturn the results of the last presidential election—that it was unthinkable he would win the presidency for a second term. Yet the problem of Trump lies precisely in those qualifications—misogyny, white supremacy, and plunder—that have historically animated the relationship of white America to the rest of the country. It is the problem of Jim Crow, interpreting the civil rights laws of the emancipation era to mean their opposite. It is the problem of anti-Blackness, rendering Black political organizing as fraud and even rioting. But most of all, it is a problem ingrained in the American Dream, one of accumulating wealth and security at the expense of others.

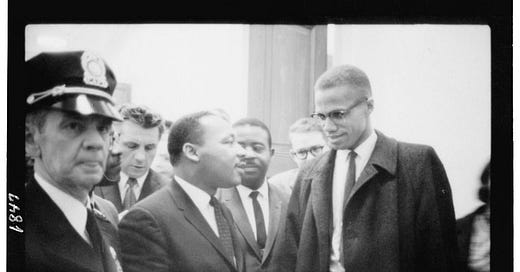

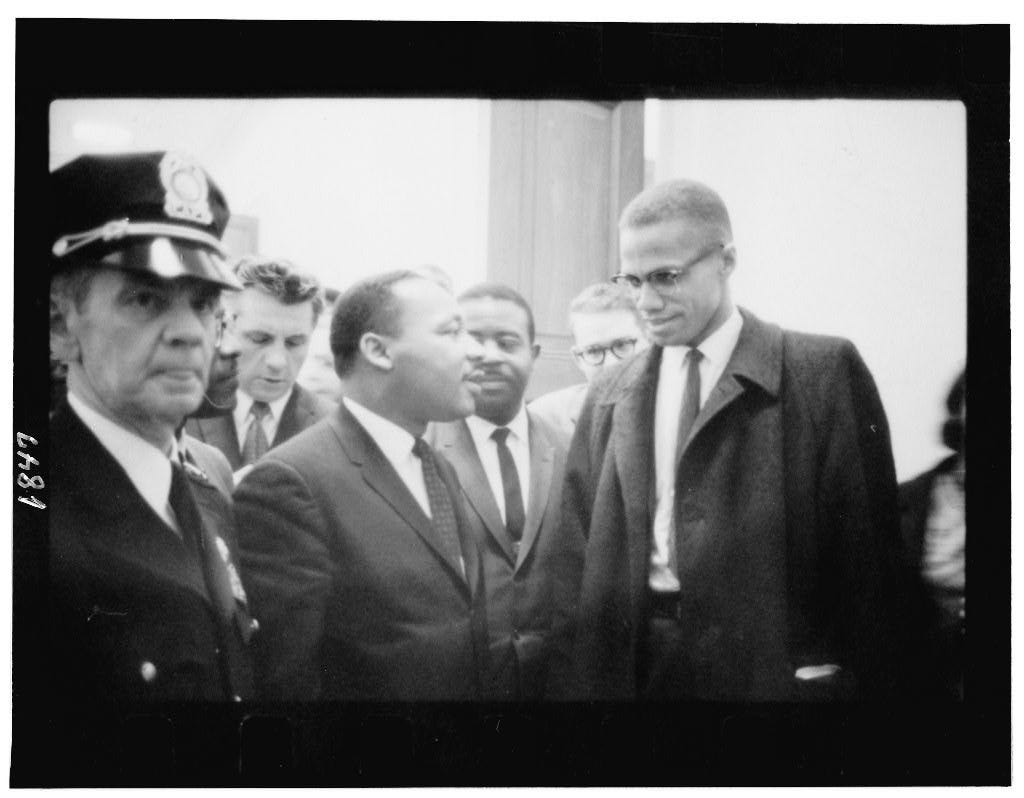

In the story America likes to tell about itself, it is the land of the free and the home of the brave and has stood for liberty and equality since the Declaration of Independence. Slavery, annexing a third of Mexico, “Indian removal,” Japanese Internment, Jim Crow, etc. are rendered minor misunderstandings. Yet the luminaries of the Civil Rights Era have always told a different story. “I’m speaking as a victim of this American system,” Malcolm X explained, “And I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.” Or as Dr. Martin Luther King put it, “it’s a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.” “America was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and Midwest,” King pointed out, “which meant that there was a willingness to give the white peasants from Europe an economic base.” No such redistribution of stolen land benefited Black America, who were not legally citizens at the time of the Homestead Act, or other racialized groups, for that matter. Whatever their differences, Dr. King and Malcolm X both accurately understood the American Dream of upward mobility to be grounded in racialized plunder.

In many respects, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s achieved stunning victories, which could support a democratic mythos were they not violently opposed and undone by white conservatives. Organizers won the right to representation enforced by the federal government, undone by the Supreme Court in its 2013 Shelby County vs. Holder ruling. Civil rights activists secured the right to fair housing after generations of state-sponsored housing discrimination, limited by the Supreme Court in the 2015 Texas Dept. of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, Inc. ruling. They won the right to integrated education, undermined by Milliken v. Bradley (1974), a legal right to equality in “affirmative action,” overturned by SFFA v. Harvard/UNC (2023), and an immigration system not totally determined by racism, being undone as we speak. Incredible (if incomplete) civil rights victories in the 20th century have been chipped away in the 21st century by people claiming to support a vision of rights “deeply rooted in [our] history and tradition” of slavery, segregation, forced sterilization, nativism, patriarchy, and genocide.

So if America really has always been about freedom and equality, with systems of inequality representing merely minor misunderstandings, how do we explain that the first era of civil rights legislation in the late 1860s ended with mass violence and a shrug from white America? The civil rights rulings of the 1960s, after all, relied on laws and amendments passed by Congress a century earlier, during Reconstruction. These laws—especially the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments, the Civil Rights Acts, and the Reconstruction Acts—had been advanced by Black activists during the Civil War and its immediate aftermath. They granted Black Americans citizenship as well as allowing them the right to vote and hold public office, serve on juries, marry, and found schools, churches, and communities. In response, white conservatives burned down Black schools, lynched Black politicians and their white allies, and engaged in widespread voter suppression and violence. White conservatives organized election denial schemes and coups. They even massacred all the Black officeholders and their families in Colfax, Louisiana, which the Supreme Court later ruled had not violated victims’ civil rights.

If America’s greatness is its love of freedom, who led the massacre of voting rights activists in New Orleans? Who organized the Red Shirts to gun down Black voters in South Carolina? Who held the firehoses in Birmingham? Who wielded clubs on Edmund Pettus Bridge? Who opened fire on protesting college students from an armored vehicle at Southern University? Who dropped a bomb on a Black neighborhood in Philadelphia? Who demanded that the military shoot Black Lives Matter protesters? Governors. Cops. The president-elect.

Americans need to stop lying about what this country has been. The lie of democracy, equality, and the American Dream may make some of us feel better about ourselves as those in power pick the pockets of those around us. But the “convenient fairy tale,” as W.E.B. Du Bois called it, prevents the United States from actually becoming a country based on opportunity instead of racialized theft, equality rather than racial and gendered oppression.

I want to close with a few lines from my recent article, “Necessary Utopias: Black Agitation and Human Survival,” on the utopian organizing and implementation embedded in the egalitarian struggles of Black radicals from emancipation through the civil rights movement. These visionaries not only saw white America as it was, but also imagined and brought into being new worlds premised on equality and possibility. They represent, in many respects, the best of who we are and might become:

What remains an open question for us to answer is how to speak and to act—how to implement a utopian praxis capable of seizing a livable future for one another and our communities. That praxis is in fact a three-fold process, first an assessment and critique of the world as it exists, second a sabotage of those existing systems grounded in an alternate vision of the future, and third the construction of an infrastructure capable of sustaining life. While we might sketch out some of the possibilities in mutual aid, in work stoppages, in self-determination, and in organizing, to do so here might be counterproductive since this new world should be born democratically, from the demands and desires of our communities. As Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin puts it, the “people themselves must be in command, not leaders” (Ervin, 2021, p. 35). What we can say for certain, however, is that the history of these utopian movements, from emancipation and civil rights through ongoing movements for racial, economic, gender, and climate justice, show that this type of organizing can be successful and illustrate the possibilities for the struggles of today.

It is crucial that we look carefully and honestly at the way that racialized and gendered violence and plunder have shaped American history. They have been defining features of our shared past. Yet those who fought valiantly against these systems of oppression, winning seemingly impossible victories, offer tactics for the present and hope for the future. If chattel slavery could be destroyed and Jim Crow dismantled, what is possible for those of us willing to take up the struggle today? What new worlds might we bring into existence for ourselves and one another?

In love and solidarity, always.